Lesen Sie diesen Text auf Deutsch

It’s like someone is pounding on Nele’s

knee with a hammer as hard as they can, over and over again. “It’s a dull

pain,” she says, unsure whether “dull” is the right word.

It is a feeling she has known for 26 years.

It’s with her every hour, every minute. On bad days, it can feel like a

bulldozer is driving over her legs. Sometimes, it’s like someone is stabbing

her knees with a knife. At others, like a flamethrower is being aimed at her

joints. These are the images Nele has come up with to describe to doctors what

is wrong with her.

It was the summer of 1992, the air outside

smelled like sunblock and raspberry bushes. Nele was seven years old, and like

she did so often that year, she headed out with her friends to clamber around

in the forest. There was this one boulder that had roots coming off it like

bristly hairs you could grab onto. It was no bigger than 4 meters (13 feet),

but you needed skill and stamina to make it all the way to the top. Nele was

one of the best at it. When the tiny girl proudly stood on top, watching the

others as they climbed, her blond ponytail would bob jauntily in the wind. Almost

every day, she came home with ticks, often 10 or 15. Her mother would pull them

out with tweezers, and she had so much experience doing so that men from the

neighborhood would sometimes come by when one of the parasites had burrowed

into their skin. But that was the last day she would pull out ticks. She would no longer be able do so.

“Only a Children’s Flu”

It started with a headache and then came

the fever. The family doctor sent the girl home. “It’s only a children’s

flu,” he said, creasing his brow. But the headaches grew worse and the

fever got higher. The doctor’s creases deepened into furrows. Nele didn’t cry.

She wanted to be a brave girl, as she had learned from her big family and

churlish cousins. But when she began showing signs of localized paralysis, her

mother took her to a clinic. The staff there had no experience with symptoms

like Nele’s, so her files were sent to specialists in the United States who

diagnosed it as Lyme disease.

The odds of contracting Lyme disease are

not altogether low. According to the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), a German

government agency responsible for disease control and prevention, up to 30

percent of ticks in some parts of Germany carry the pathogens that cause the

disease. Starting in early summer, they multiply, especially in Germany’s south

and southwest, preferring to live in the tall grasses on the edges of forests. Studies

show that between 80,000 and 200,000 people are infected with the borrelia

bacteria every year. They can attack various organ systems, and usually take

aim at the skin, the nervous system and joints. Those infected suffer from

fatigue, muscle and joint pain, and swollen lymph nodes. It feels like the beginnings

of a bad flu. But, unlike the flu, there is no vaccination against Lyme

disease, and sometimes no cure. Symptoms include in rare cases paralysis or arthritic pain that can move to different parts of the body and persist for years.

Like Flames on a Wall

These days, treatments for the disease have

an increasing success rate, but that wasn’t the case in 1992. Nele’s parents bought

a binder for their daughter’s medical files, but it soon filled up and they had

to get another. In the hospital, the seven-year-old was treated with

antibiotics, which seemed to help. But a few weeks later, the pain arrived and never

went away. She had pangs in her legs and they would grow stiff, and then the

sensation would shoot up her body to her hips – fast, overpowering and scary,

like flames up a wall. The burning, hammering and stabbing, as Nele describes

it, were so intense she became nauseated. When she squatted down, she often

needed help getting back up. Eventually, Nele had trouble walking. The borrelia

bacteria were still inside her, but this time, they had attacked her joints

instead of her nervous system. Again, she was treated with antibiotics and her results of the blood tests normalized. But although Nele was healthy on paper, the pain

remained. Like mites in a mattress, it had infested her limbs. The doctors

didn’t know what to do.

Nele’s father drove with her across

Germany. GPS navigation didn’t yet exist, so his daughter had to learn how to

read maps. There was a thick blue road atlas in the glove box and it became a

constant companion. Nele would later know the maps of some regions like the

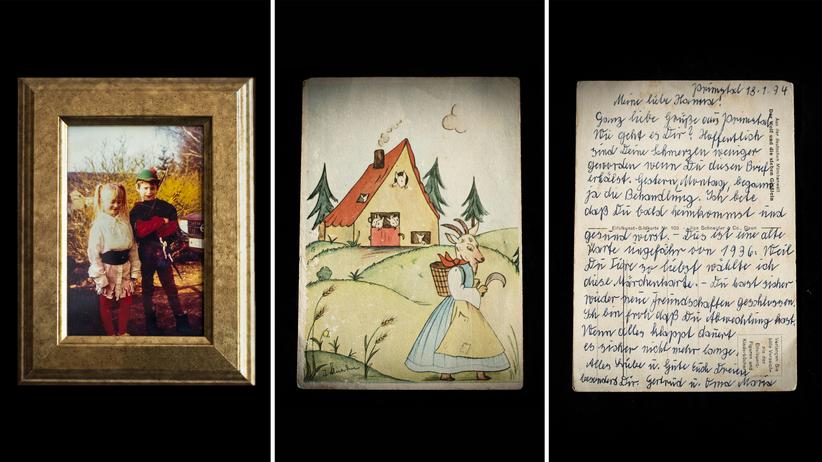

back of her hand. When she was in the hospital, her grandmother would send her “letters,”

as she called the old-fashioned, prewar postcards that were decorated with

images of wandering goats or sledding children. “Hopefully your pain has

gotten better by the time you receive this letter,” the grandmother wrote

in the mid-1990s. “I am praying that you will soon come home healthy.”

Nele loved the cards. She has kept some of them to this day, even though her

grandmother’s prayers didn’t help.

© Lena Mucha für ZEIT ONLINE

In the years that followed, Nele was

treated with antibiotics, with cortisone, with opiates, with autologous blood

transfusions. Her arms became so riddled that on some days, the doctors were

unable to find a vein to take her blood or give her an IV. Her parents tried

every therapy conventional medicine had to offer, and when that didn’t help,

all alternative therapies as well. One homeopath wanted to pull

Nele’s teeth. She was told to swing a pendulum over her food to distinguish good apples from bad apples. She got insoles for her shoes. A couple of self-proclaimed

healers laid hands on her. Another suggested a vegan diet: “Then everything

will be OK again” he said – and seemed like he was trying to convince

himself more than anything. Even Dr. Müller-Wohlfahrt, the famous team doctor for

FC Bayern Munich, sent her home. There was, after all, nothing left to

diagnose.

Hits: 385